|

|

||||||||||||||

|

COMANCHES ON THE FLY

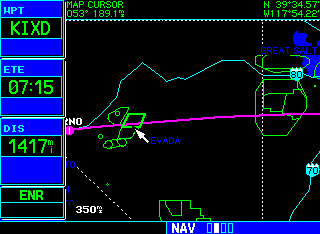

MY LONGEST FLIGHT, 8 HRS, 34 MIN IN A COMANCHE 250 by Mike Dolin Preface: At the entranceway to my hangar complex, a sign reads, "Safety First." Safety First. That's the watchword of aviation. What a way to start an article on long distance flying. But if I didn't do just that, merely giving the length of time and meaningless numbers, it would seem as only arrogant boasting. After a request to write this article, I gave it some thought. I figured the story had to read nearly like a flight lesson. What's more, I'm not sure what the big deal is, as my time-lengthy flights don't measure up to those of fellow contributors and regular long distance flyers Omri Talmon and Karl Hipp. There are frequent ocean-crossers so numerous in all kinds of airplanes. In the January '03 Comanche Flyer, a reprint article recalls Tom Smith's much longer flight, 11 hours 20 minutes in his Twin Comanche with Capco tanks. And our long distance Comanche flying hero is none other than Max Conrad, who set records galore in his flying career. In fact, for all I know, many of you reading this do the same long-ranging, but don't come out of the closet to write about it. That is such a shame, because the flight experiences of many Comanche fliers are so rich in color and so fascinating to fellow pilots, that they ought to be shared. Once more I describe my mount as a stock Comanche 250 with the factory installed ever-so-common 90-gallon tanks. I have gotten quite used to having excess fuel range. Mine is a '62 airplane not so far off from the middle of factory deliveries in serial number. Since buying it I have installed a handful of meaningless speed mods (which someday I'll have to take up with Hans Neubert). It has an average stack of IFR radios that I hate to admit are becoming dated. Like so many Comanches, I like to think mine is well cared for. Hurdles: I'm going to offer a few keywords right up front. Absolute hurdles for some flying folks. Oxygen. Pee-bottle. Cockpit confinement for long hours. Fuel management. If you find these words unappealing, or even objectionable, perhaps you shouldn't entertain the idea of long distance flying. The trips are tiring, the data monitoring becomes exacting, and the sum total is relatively expensive. But we all know that, as high performance aircraft owners. We know what we're getting into. In fact you can put me on the borderline if you will. To go the same distance in an automobile, I find totally revolting. I should mention that the oxygen downside for most pilots is the initial pain in the pocketbook. Wearing a nasal canula is actually fairly comfortable. Once I tried to exit my airplane while still wearing one. They are pretty low cost and approved to an altitude of 18,000 feet. The oxygen subject is detailed with many variations and rules. Search 91.211 for flight rule details. The next item mentioned, a pee-bottle, is self-explanatory. Some folk absolutely refuse to talk about it, declaring it a very personal issue. Either you will or won't. I no longer understand how a pilot can fly a complicated instrument approach facing a possible go-around, with "personal hyrdaulic pressure" producing discomfort. My airplace hat shelf is stacked with relief bottles. Examples of long-distancing hardship: Years ago, I repeatedly flew my Comanche from Ft. Lauderdale to Cleveland, Ohio where much of my family lives. The flight ranges in time from a short 5-1/2 hours to maybe over 8, once requiring a fuel stop. It depends on winds, of course. I take the winds as they come when traveling. I usually can't wait for the day when winds are going my way. On occasion, I would stop in Charleston, South Carolina to pick up my sister and brother-in-law and bring them along. From Charlie South, the flight to Ohio is generally 4 hours. After a number of these two-way flights, Marlene asked if we could stop halfway for an en route break. So you see, she's not one to endure the discomfort of long distance flying. Once she put on a nasal canula for high altitude, not minding that at all, but she finds long hours in the cabin unappealing. I explained that Charleston, West Virginia was the only logical en route stop with a measure of convenience. Over the Appalachian Mountains, there are not many airports between Charlie South and Cleveland. The result is a flight of fully three hours to Charlie West with more than an hour to go. But in reality, one four-hour flight turns into a three-hour flight plus a two-hour flight. That's the flight time only. Another hour on the ground makes it a day of travel, getting to the destination. We did just that, one time, and could see how it stretched the traveling day. To confirm this line of opinion, a local Baron pilot writes that he runs lean of peak (LOP) declaring that a fuel stop adds another 60 minutes to his trip. He doesn't otherwise have the range to fly from Kansas City to Florida. Great! Duly noted, he slows down his much faster airplane in order not to stop for fuel. More often than not, I use my airplane for scheduled travel, mostly. My steed gets me from place to place as needed at the time with a window that varies perhaps a day or two. Just like this longest trip. Thus, my own preference has always been to fly at very high altitudes for the whole distance to where I'm going, then put the airplane away once at journey's end. I prefer that to stopping en route. The destination has always been the goal and if I can avoid fuel stops on lengthy trips, I figure it is saving time overall. Not to call it time wasted, though, when an en route stop looks interesting enough to stay, that becomes the new destination. About fuel range and management: The regs to remember are VFR 91.151 and IFR 91.167. The FAA rule states that there must be a half-hour of cruise fuel on board when the tires kiss the pavement. Exactly how much fuel that really is, is subject to discussion. But many would agree it's around 6 gallons for the Comanche 250. Long before the half-hour mark though, I have a pretty good plan of knowing what to do. Long distance fuel management is not rocket science. To leave two or three gallons remaining per tank in a multiple tank Comanche is to run yourself short of long range achievement by an hour or more. Once a tank is down that low, the remaining fuel is a dead issue. If not used up in smooth air, you cannot safely switch back to a low tank for approach and landing. Many pilots clain to have a comfortable limit of how much fuel they will use. If you must, set your higher limits and stick to your plan. Be safe. Some say they will never run a tank dry on multiple tank airplanes and they must have more than an hour of fuel remaining in the last tank upon landing. Be comfortable with your limits keeping safety in mind. But to give yourself arbitrary limits and then find you are stretching them when nearing a destination is not to have limits at all. It serves no purpose to stretch a flight into risky thin reserves. The accident files are filled with fuel mishaps. Accident reports differentiate fuel exhaustion from fuel starvation. Exhaustion occurs when no fuel is left. Starvation is when fuel is on board at the crash site, perhaps spread around in various tanks, but not fed to the engine. It's so important to dwell on fuel management. To run a tank dry and catch it in time does take some concentration. Unless I dry up each tank in turn, I have no idea of exactly how much fuel is left in any particular one. Ever since buying my Comanche back in '74, I marveled at its long range. Six hours seemed the safe fuel limit back then, not that I used this capability at first. It was comforting to know I had extra range or could go to a destination and back without refueling. But when the call came for long distance flying, by tweaking my fuel management procedures, plus buying a portable oxygen system, I have squeezed so much more time out of those tanks. Soon I learned how to run a tank dry without the engine missing a lick. How did this happen? By repeated practice. Yearly, I would fly the trek from Ft. Lauderdale to Cleveland, another to the ICS convention,. wherever that would be, and for a couple of years, I flew from south Florida to New Joisey regularly. These flights often stretched to six or seven hours. My logbook shows longer length trips since moving to Kansas City. Natch. KC, deep in the heart of the heartland, is further from anywhere else in this country. Each long flight turned out longer than the previous. Recording 7 hours 51 minutes once, I thought that was the limit. That was before Reno. So I learned to manage distance to the max. But please notice that I don't go overboard. In the article previously written I state that I planned a fuel stop on the way to San Francisco. If I have to make an unplanned stop for fuel because of headwinds I do just that. Perhaps I hate to get back in the plane, restart and begin another flight that same day, but the Safety-First rule must prevail. Would I want to add more range to my airplane? After all, there are no less than three separate STC fuel tank ad-ons that I know of. Lordy NO! After 10 hours in the cockpit, I'd probably forget my own name. Plus the airplane is heavy enough, carrying around 540 lbs. of gas as it is. Preflight Planning: Whether aggravating headwinds or welcome tailwinds, I flight plan for all contingencies, then give it a go. Another regulation is Preflight Action. 91.103. The catchall phrase in the reg is that we must learn "ALL" there is to know about the intended flight. Let's do that in our preparation, from a study of the en route geography to the weather, winds, available airports and fuel planning. This flight was treated like any other across the United States; long distances over variable terrain, any kind of weather, airports galore for impromptu fuel stops. Thankfully, we have friendlier skies here than do pilots who fly across oceans or over vast stretches fo open country. Many of you have your own favorite flight planning software. I start my own planning on the GPS 500 series simulator that Garmin offers for free. I choose the GPS 500 set up because the screen is bigger. You can easily do this on a protable GPS unit as well. At many educational safety seminars, the moderator has said, "Do you flight plan the proper way, drawing a line on a chart, or do you just use a GPS?" How shortsighted, this empty statement. Yet this seems the prevailing mood by some officials. If you merely enter a GO-TO waypoint in your GPS, then you're adding fuel to their fire. You miss a whole world of high tech benefit that GPS adds to your planning. Contrary to the official's stated opinion, I find something the GPS is very good at that isn't easy to do on charts. The GPS finds the ever so tiny restricted airspaces dotted around the western states that barely show up on paper. The GPS aslo differentiates between restricted and alert areas, shown as the same color on Low Alt Charts. What's more, in flight the GPS continually counts the miles and minutes to destination, saving us countless calculations. For those of us who still keep an in-flight track log, that is. Later, on the Internet, I can check fuel prices, weather and notams. On the GPS 500 simulator the first thing I do is create a route from home to the destination(s). I have set the restricted areas and class B to display on all ranges, filtering out the class C, D and MOAs for now. Generally there are restricted areas aplenty on flights west, and the ultimate route line is anything but straight. Thus GO-TO doesn't fly in the long run, especially when considering the return flight to home base. (Can you say INVERT or Reverse Route?) This flight proceeded to Prescott, AZ for the first RON. Then on to Reno, (KRNO) a day later, and return to KIXD the following weekend. At this time I'll show you how I planned the flight from KRNO to KIXD. Now, pilots, what is the first thing we learned about cross-country flight planning as children back in flight school? We drew a line on the chart and measured the distance. Right? Well, if we look at the illustration, a one-leg route is not only a curved line, but it will go through some seriously restricted airspace.

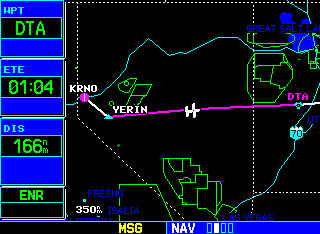

The next thing to do is zoom in and look around for convenient waypoints. At some length I found that a route to YERIN, then DTA, then direct to KIXD kept me out of all restrictions. Zooming in on YERIN shows the way to go in the clear. The simulated airplane is flying off scale in this screen shot, so don't try to make much sense out of the numbers.

The simulator (and your GPS) adds up total distance of the legs as you go. This one comes out to 135 statute miles total, (1173 nautical). In the next photo, the little simulated airplane merrily wends its way to Delta VOR (DTA) in Utah. See area 51 and the restricted complex in Nevada to the south of this route. Before too much confusion develops, I must say that this free simulator only simulates navigating the Garmin 500 series GPS. The little airplane symbol flies a route or GO-TO at whatever speed you assign to it. You can watch it fly over your route in real-time. What it isn't is this: It is not desktop instrument software that you fly like an airplane with yoke and rudder pedals.

Later, I like to lay the charts out on my living room floor to mark the route, circling VOR and NDB stations, restricted area numbers and any other elements worthy of note. Personally, I love the geography lesson, scanning names of places I've not been to before. Why not enjoy the planning stages? A well planned flight usually goes off without a hitch. Whether you use the E6-B function in the GPS or another computer, or even a cheapie calculator, you have time/distance/fuel calculations available at your fingertips. My fuel-planning failsafe stops would be Manhattan, Topeka and Gardner, all in Kansas. The land looks desolate to some, but my route was replete with airports along the way. The flight: I loaded the airplane the night before, mostly because of little room in the rental car. In effect, we carried stuff from the hotel to the airport in shifts. That gave me a chance to look over the airplane and check that the fuel tanks were full. Even though I flew alone, the airplane was loaded fully to gross weight with excess baggage. I tried to organize the cabin as best I could. It was totally covered with desert dust. Absolutely filthy! I loathe flying this airplane so dirty, but there was neither time nor availability to wash it. The main Reno event that weekend was the Reno Air Races. The parking ramp was overflowing with dirty airplanes. Sunday morning when I got to the airport, a line of planes was already waiting for take off. Line service was pulling each plane off the dirt onto the hard surface ramp, one at a time. Some of the ICS people had moved their airplanes to outlying airfields for convenience before the day of departure. Great idea. A class C clearance before taxi plus long waits before takeoff mark the Reno departures. Unlike those of far busier Lakeland and Oshkosh where airshow controllers scoot you out quickly, Reno delays seemed longer than necessary. Take off from runway 16 Right headed me nearly straight for YERIN. Reno Departure wasn't likely to send me off in some unwanted direction as I have come to experience at other airports. Soon I said goodbye to departure and headed on my own navigation alon the flight planned route line. The climb to 15,500 feet took a while, but with patience, the plane got there and hung on just fine. My engine operating and leaning practices are as routine as any. I don't try to squeeze exceptionally low RPM or lean of peak (LOP) operation out of it. This engine has a carburetor, for which I understand LOP is not recommended anyway. There was no wind to speak of, but then, no real weather either, for which I was grateful. I sat in the driver's seat ruminating about the 2002 ICS convention and the Reno Air Races. It was definitely worth staying for the races if you've never seen them before. I'm not alone in modern man's quest for speed. However, I do seem to lag behind in actually finding it. The flight was enjoyable, a bit long, but mostly anticlimactic. I stayed at 15,500 feet for the entire length. Nearly all there is to do is look at scenery and listen to music the entire time. Some pilots prefer to be in contact with flight following, but after an occasional check of en route weather, I chose not to call them. It's amazing that the machine runs along, avionics and all, for so long a time without a whimper. What stretching routine or exercises does one do in the plane to keep bodily fluids circulating? Do you prepare for such a long stint in the cockpit by exerxising and remaining fit? Or do you get ready for long periods of inactivity by sitting in front of a TV set, drinking beer? To be honest, I never gave this much thought. I once read in a magazine article, recommended exercises that a doctor suggested, and even tried the stretching routine in the pilot seat, one limb at a time. But fro the most part, I think a pilot must be inclined toward flying long distances rather than training for it. I might add, that my inclination for long flights comes and goes. There were times when a three-hour trip felt too long. On the other hand, when looking forward to traveling far away, making the long flight was actually exciting. Never in my lifetime did a flight coming home feel as goos ad the one going to a destination, and this particular one was coming home. After landing, it took 81.7 gallons of gas to fly the 8 hours and 34 minutes. I'm sure there were another 45 minutes available in the last fuel tank upon landing. That means I could have selected any airport in the Kansas City area, which is within 15 minutes of extar range, but certainly not any city further. I landed before dark, even though covering two time zones eastward. After refueling at home base, I was too tired, too exhausted or too bummed out to get back into the airplane. I asked the FBO to tow my plane back to the hangar. After buying $200 of gas from them, and describing the story I have just written above, they were quite gracious about it. I rode on the tug all the way back. I can't remember if I emptied the airplane that day or not. One of the high points of having a hangar is that you can wait until a day when you're refreshed to "post flight the trip" so to speak. After figuring the flight numbers I found the average ground speed to be 136 knots or 157 miles per hour. "Yeah, ain't it a bitch?" Yecch! Believe me, folks, I'd rather be telling you how amazed I could be at such ferocious ground speed than how long I sat in the saddle. So the weather gods gave us headwinds that day. What are you gonna do? In this part of the country, over the same Colorado Mountains I have seen 253 mph (253 sounds faster than 220 knots, so I like to figure in mph) but once in a while, headwinds are found going east. During the flight I talked with Daryl Norris and Rich Bullock, who were somewhere within radio range. Daryl was flying his Comanche 260B with the Lopresti cowl and speed mods. He said he figured a few knots of headwind. Rich backed this up with a similar in-flight comment from his Twin Comanche. Oxygen quantity: I used up two large E-size cylinders that whole trip to Reno and back. I carried along three oxygen tanks. I have no idea how many cubic feet that is, but one cylinder lasts about the whole flight. Some folks declared they used very little 02 compared to me, while they talk of oxymizers and flow charts. I'm afraid I don't have scientific numbers for usage. A reading of three LPM on the guage feels about right. I just loas as many E-cylinders in the plane as I feel necessary plus an extra and turn up the flow to feel comfortable aloft. At no time do I try to exonomize. I figure oxygen is like fuel, I'm not going to start a flight with less than all fuel tanks and E-cylinders topped off. When I buy an exchange cylinder it doesn't matter if the one I used is empty or partially filled. It all costs the same. Post flight: As I said at the start, there is really nothing out of the ordinary about this flight. All credit goes to the Comanche 250, this quite standard marvel from ole man Piper. My only claim is having learned to approach maximum use of the range. If anyone wants to talk with me about any part of this flight or related matters, my e-mail address is mike.dolin@garmin.com We can discuss fuel management.

Or any othe subjects you'd care to discuss. Send me your phone number and we'll chat on the weekend.

Mike and the Comanche 250. When not flying around the countryside or polishing up the paint job, Mike spends his spare time working at Garmin.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||